Azerbaijan turns to deep gas at ACG as Europe seeks new energy supplies

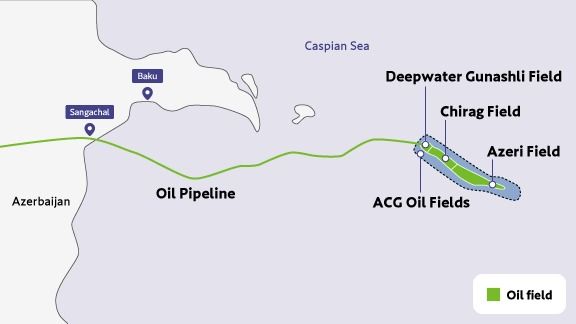

For Azerbaijan, the next chapter in its energy story may be written not in oil but in gas discovered deep beneath one of its most celebrated oilfields. This year, BP and its partners plan to begin producing natural gas from reservoirs never before tapped in the Azeri-Chirag-Gunashli (ACG) block of the Caspian Sea, a move that could reshape both the country’s domestic energy mix and its export strategy.

The significance of this development was underlined by Bakhtiyar Aslanbeyli, BP’s vice-president for communications and external relations in the Caspian region, who said that data from a well drilled last year from the West Chirag platform has yielded “very valuable information” about untapped gas layers.

These lie beneath the oil-producing horizons that have dominated ACG’s output for decades. One such layer, known as Kirmakıüstü Gumlu, lies relatively shallow; another, Kirmakıalti, sits deeper still. Initial gas extraction from the latter is expected in the first half of 2026, with broader production from the more accessible Kirmakıüstü Gumlu formation planned for the second half of the year.

This shift to gas in a field better known for oil represents a strategic pivot for Azerbaijan’s energy sector. The ACG block, which first began production in the late 1990s, remains one of the country’s most prolific sources, having yielded hundreds of millions of barrels over its life and underpinning Baku’s export capabilities. Alongside Shah Deniz and the emerging Absheron gas field, ACG’s gas output will help Azerbaijan meet growing demand in Europe and strengthen its role as a reliable supplier at a time when markets seek alternatives to Russian supplies.

The potential prize beneath the Caspian is substantial. According to BP, the newly identified non-associated gas (gas not tied to oil production) could include as much as 4 trillion cubic feet, or roughly 113 billion cubic metres, a volume that, if commercially productive, could add meaningful capacity to Azerbaijan’s export portfolio.

That possibility only opened recently. In September 2024, Azerbaijan’s parliament ratified an amendment to the existing ACG production-sharing agreement, allowing for the exploration, evaluation, development and production of these deep gas reserves. Under the updated contract, the same consortium that has long operated ACG, led by BP with stakes for SOCAR, MOL, Inpex, ExxonMobil, TPAO, Itochu, and ONGC Videsh, will bring the new gas resources into play.

Already, the first deep well, drilled from the West Chirag platform, has been completed, and completion work is underway ahead of a planned start of production by late 2025. Early testing suggests the well will successfully flow gas to surface, after tie-in works and equipment installation are finished.

The timing of this new gas output could hardly be more opportune. Global markets are tightening fast, with Europe in particular seeking to diversify supplies following Russia’s war in Ukraine and subsequent efforts to end reliance on Moscow’s energy exports. Azerbaijan has already increased its gas exports in recent years, and additional volumes from ACG may provide breathing room as infrastructure bottlenecks, such as capacity limits on the Trans-Adriatic Pipeline, constrain growth from other fields like Shah Deniz.

Analysts see this gas yield as part of a broader strategy to keep Azerbaijan’s production sustainable over the coming decade. Agencies such as Fitch expect national gas output to rise to more than 50 billion cubic metres in 2025, supported in part by new production at ACG, before levelling off moderately in 2026. The continued contribution of ACG’s oil output remains central to this forecast.

For a country long defined internationally by its oil, the transition to gas marks both an economic and diplomatic milestone. It diversifies Azerbaijan’s export base and gives it a stronger hand in regional energy affairs, particularly as Europe recalibrates its import patterns. Whether this new source will ultimately unlock a more ambitious gas export strategy remains to be seen, but for now it adds another layer to Azerbaijan’s evolving place in the global energy map.

What could this mean for Azerbaijan’s production strategy?

If commercially viable at scale, gas production from the deeper layers of Azeri-Chirag-Gunashli would mark a subtle but significant shift in Azerbaijan’s energy trajectory. For decades, ACG has been synonymous with oil, forming the backbone of state revenues and export flows. Tapping non-associated gas from the same block offers a way to extend the economic life of a mature asset at a time when oil output is gradually declining and global energy markets are changing.

In practical terms, even modest gas volumes from ACG could help stabilise overall hydrocarbon production in the second half of the decade. Azerbaijan has already relied heavily on Shah Deniz for gas exports, while newer fields such as Absheron are still ramping up. Gas from ACG would not replace these sources, but it could act as a buffer, smoothing fluctuations, supporting domestic demand, and freeing up additional volumes for export.

There are also infrastructure implications. Because ACG is already integrated into Azerbaijan’s offshore production system, developing gas there may prove faster and less capital-intensive than launching a greenfield project. Analysts note that this could allow Baku to incrementally raise output without the long lead times typically associated with new offshore gas developments in the Caspian.

From a geopolitical perspective, the timing is notable. Europe continues to look for incremental, politically reliable gas supplies as it reduces dependence on Russia. While ACG gas alone would not transform Europe’s energy balance, it could strengthen Azerbaijan’s position as a flexible supplier capable of adding volumes when market conditions allow, particularly once pipeline bottlenecks are eased.

At home, the implications may be just as important. Additional gas production could support electricity generation, reduce seasonal pressure on supplies, and reinforce Azerbaijan’s ambition to use gas as a transition fuel alongside investments in renewables. That, in turn, could give policymakers more room to manage energy exports without undermining domestic stability.

None of this is guaranteed. The initial production phase is explicitly described as testing, and the deeper Kirmakıalti layer will be short-lived. Much depends on reservoir performance, costs, and global gas prices. But taken together, the discovery suggests that Azerbaijan’s most famous oilfield may yet play a role in shaping the country’s gas future, long after its oil peak has passed.

Here we are to serve you with news right now. It does not cost much, but worth your attention.

Choose to support open, independent, quality journalism and subscribe on a monthly basis.

By subscribing to our online newspaper, you can have full digital access to all news, analysis, and much more.

You can also follow AzerNEWS on Twitter @AzerNewsAz or Facebook @AzerNewsNewspaper

Thank you!