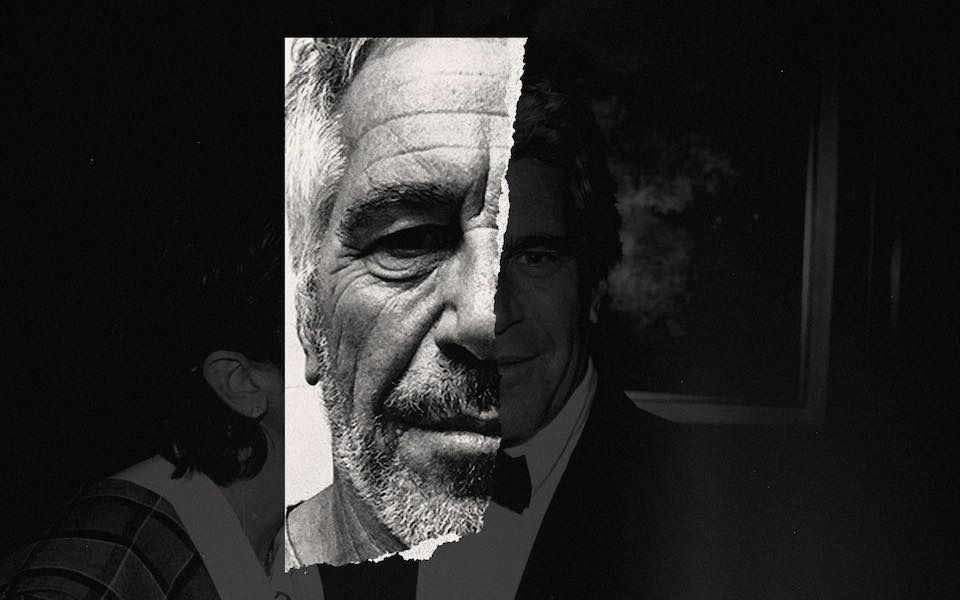

Could Epstein scandal accelerate rise of populist power?

Epstein’s enduring power lay not in wealth alone, but in his role as a social and financial intermediary. He operated at the junction of money, politics, philanthropy, and academia, spaces where informal trust often substitutes for formal accountability. His presence exposed how elite networks function less like meritocratic ladders and more like closed circuits, where reputations are laundered through proximity to power. When those circuits fracture, the damage spreads far beyond individual wrongdoing.

The renewed focus on Epstein arrives at a moment when public patience with corporate and political elites is already thin. Inflation shocks, widening inequality, and the perception that globalization enriched insiders while hollowing out middle classes have primed societies for moral outrage. In this climate, Epstein’s files are not merely legal documents; they are political ammunition. They allow critics to personalize abstract grievances about “the system” by attaching them to recognizable names and institutions.

For decades, global business leaders defended their dominance with a simple bargain: markets would deliver efficiency and prosperity, and elites would manage complexity responsibly. That bargain has frayed. ESG campaigns, diversity pledges, and philanthro-capitalism were meant to restore legitimacy, but in the Epstein context, they backfire. When figures associated with moral posturing are revealed to have tolerated or concealed abuse, the charge of hypocrisy becomes far more potent than allegations of greed alone.

Not all elites suffer equally. Those whose authority rests on technocratic competence or moral signaling are more vulnerable than openly transactional figures. This explains why reputational damage clusters around bankers, consultants, and institutional leaders rather than populist businessmen or political disruptors. The scandal thus accelerates an internal sorting process within the elite: credibility now depends less on virtue signaling and more on raw power, loyalty, or cultural alignment.

The case also intersects with international politics. Allegations involving lobbying, intelligence-adjacent figures, and cross-border financial flows reinforce suspicions that Western elites play by different rules. For non-Western audiences, and for governments critical of liberal internationalism (globalism), Epstein becomes proof that the moral authority of the West is compromised. This weakens its ability to lecture others on governance, corruption, or human rights.

UK as an example

Keir Starmer's premiership was hanging by a thread on Thursday after a revolt by MPs in his Labour Party further damaged the already troubled operations at 10 Downing Street, which have been staggering from crisis to crisis.

Starmer attempted to clarify his earlier statement in parliament on Wednesday regarding his knowledge of the friendship between former Cabinet minister Peter Mandelson and Jeffrey Epstein. Despite this connection, Starmer had still appointed Mandelson as ambassador to Washington. “It had been publicly known for some time that Mandelson knew Epstein, but none of us knew the depth and darkness of that relationship,” the Prime Minister told reporters.

Starmer had fired Mandelson last year after the release of Epstein files indicated that Mandelson continued to support his friend even after Epstein was convicted of sex offenses in Florida in 2008. However, the scandal resurfaced this week when newly disclosed files suggested that Mandelson may have leaked secret and market-sensitive information to Epstein during the height of the 2008 financial crisis, which would have been highly valuable to Epstein and his Wall Street associates. Mandelson is now facing a criminal investigation and has resigned from both the House of Lords and the Labour Party.

“Mandelson betrayed our country, our parliament, and my party,” Starmer stated in parliament on Wednesday.

A day later, Starmer vowed to remain in his position despite growing questions regarding his judgment. He expressed his apologies to victims of Epstein: “I am sorry. Sorry for what was done to you. Sorry that so many people in power failed you. Sorry for having believed Mandelson’s lies and appointed him,” Starmer said. “But I also want to convey this: In this country, we will not look away. We will not shrug our shoulders, and we will not allow the powerful to treat justice as optional. We will pursue the truth. We will uphold the integrity of public life. And we will do everything in our power, in the interests of justice, to ensure accountability is delivered.”

Mandelson issued an apology for his relationship with Epstein in a statement to the BBC last month: “I was wrong to believe him after his conviction and to continue my association with him afterward. I apologize unequivocally to the women and girls who suffered.”

He mentioned this week that he resigned from the Labour Party to spare it “further embarrassment.”

However, Starmer’s anger does not fully explain why the fallout from the Epstein scandal seems more severe in Britain than in Washington, where the files were released. The reality is that the storm brewing in Britain is not solely about Epstein and his alleged trafficking and abuse of young girls. Instead, it is a scandal that is exacerbating a trio of ongoing melodramas already dominating British politics, media, and public life.

This narrative revolves around a Prime Minister who has been on borrowed political time, less than two years after winning a landslide election victory. His challenging performance in parliament on Wednesday has hardened perceptions of a leader on the brink and increased speculation about a potential leadership challenge from within the Labour Party.

As The Economist suggests, a delegitimized elite creates fertile ground for populism. Leaders like Donald Trump do not need to prove the guilt of every figure named; the mere existence of the network validates their narrative of a corrupt establishment. Policy moves targeting corporations, even when symbolic, gain traction because they resonate emotionally with voters who see big business as unaccountable and insulated from consequences.

Perhaps the most consequential dimension is what follows. History shows that elites rarely disappear, they are replaced. The next cohort, drawn from technology, artificial intelligence, and “effective altruism,” promises efficiency and disruption rather than globalization and free trade. Yet they inherit the same risk: opacity, concentration of power, and moral blind spots. If Epstein’s downfall teaches anything, it is that informal immunity does not last forever.

It can be hard in Washington, where presidents serve fixed terms, to appreciate the pressure on British prime ministers.

As soon as a new leader enters the famous black door in Downing Street, speculation mounts in the feverish Westminster Village about how long they will last. This mania, and behind-the-scenes plotting that haunts all PMs, has become even more intense over 11 years of turmoil in which a nation once known for political stability has burned through five prime ministers before Starmer.

The Epstein documents are not just about past crimes; they are a warning flare for future power holders. Perhaps, we now live in an era where digital trails never fade and public anger compounds quickly; proximity to scandal can be as destructive as participation in it. The ghost of Epstein lingers because it reveals a deeper truth: when elites lose moral credibility, they do not merely face scandal, they face replacement.

Here we are to serve you with news right now. It does not cost much, but worth your attention.

Choose to support open, independent, quality journalism and subscribe on a monthly basis.

By subscribing to our online newspaper, you can have full digital access to all news, analysis, and much more.

You can also follow AzerNEWS on Twitter @AzerNewsAz or Facebook @AzerNewsNewspaper

Thank you!