Russia’s war economy and revival of "human meat grinder" [ANALYSIS]

![Russia’s war economy and revival of "human meat grinder" [ANALYSIS]](https://www.azernews.az/media/2025/12/16/104f1eb0-76ba-11ef-8c1a-df523ba4.png)

In modern wars, the front line no longer begins at the trench. It begins on a smartphone screen. Recruitment videos, paid advertisements, and carefully worded promises have become as essential to warfare as tanks and artillery. Russia’s growing reliance on foreign recruits in its war against Ukraine exposes not only a manpower shortage but a deeper transformation of war itself into a transactional system where human lives are priced, marketed, and discarded.

Russia’s expanding recruitment of foreign fighters over the past year exposes a troubling continuity in how wars are still fought in the modern world. Without turning this into a polemic against Moscow, the pattern itself raises unavoidable questions: how long can a military system rely on expendable manpower, and when does this logic finally exhaust not only its human reserves, but also its political credibility?

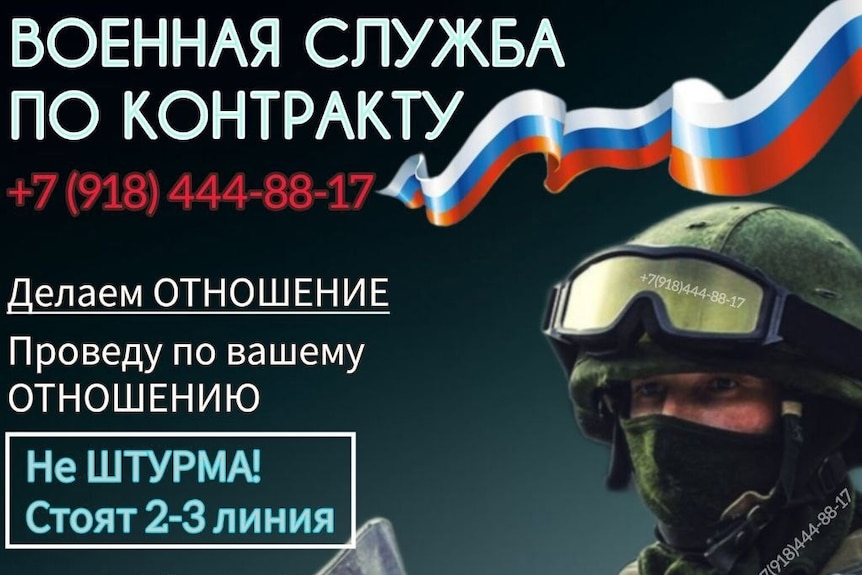

At first glance, the campaign looks pragmatic. Russia faces a growing manpower gap as the war in Ukraine drags on, and recruitment abroad appears to be a rational response. Social media advertisements in Russian target audiences across Central Asia, the Middle East, Africa, and parts of Asia, promising stable income, simplified access to citizenship, and service in so-called “non-assault” units. For many individuals living in fragile economic conditions, these offers are difficult to resist. The sums advertised dwarf local wages, and the promise of legal status in Russia functions as a powerful incentive.

This is not about condemning Russia as a state or questioning its right to defend its interests. It is about understanding a method that has deep historical roots and troubling contemporary consequences. The so-called “meat grinder” approach to warfare did not emerge yesterday. It was visible during the Second World War, when victory was often pursued through overwhelming human sacrifice. The scale of losses was so immense that even other catastrophic wars appear “smaller” by comparison. Yet those numbers represented real lives, not abstractions. Today, that logic appears to have been modernised rather than abandoned.

Over the past year, Russia has significantly intensified its recruitment of foreigners through social media platforms, particularly Russian language networks. These campaigns promise safe service, rear line duties, generous salaries, debt relief, and fast track citizenship. The messaging is deliberate and psychologically calibrated. It targets people from economically vulnerable regions, ethnic minorities, prisoners, and migrants who already live on the margins of society. The offer is simple: money, freedom, or a passport in exchange for service.

But this recruitment has increasingly taken on the characteristics of a business model. Informal intermediaries operate within ethnic communities, receiving payments for every person they recruit. In prisons, the system becomes even more brutal. Inmates are reportedly kept in harsh conditions and then offered a “choice”: go to war or remain behind bars. On paper, this is presented as an opportunity. In reality, it is coercion wrapped in bureaucracy.

Many recruits are given false, manipulative, and unrealistic information about the Russian-Ukrainian war. They are led to believe that the war is safe and that they will not be sent to the front lines, but instead will work in support roles. The promises made to recruits rarely survive first contact with reality. Many foreign fighters are deployed to the front almost immediately, regardless of assurances about non assault roles. Reports from the battlefield suggest that such fighters are often treated as expendable manpower, used to absorb enemy fire or test defensive positions. In this sense, the comparison to “cannon fodder” is not rhetorical exaggeration but an operational description.

This recruitment mechanism is particularly prevalent in Russian prisons. Ethnic individuals held in these prisons are often kept in harsh and inhumane conditions. They are then offered the chance to go to war in exchange for "release" or a reduction in their sentences.

In reality, however, mercenaries recruited into the army are commonly sent to the front lines from the very beginning and are often used as "living targets." Reports indicate that Russian officers treat these individuals as disposable assets or mere "cannon fodder."

A particularly troubling aspect of this situation is that many

recruits are registered as "missing" after their deaths. As a

result, their families do not receive any compensation or benefits

to which they might be entitled.

According to reports, many Azerbaijanis have become victims of this

deceptive recruitment. They were lured into the process by

believing in the enticing offers presented to them.

According to OpenMinds, at least 132K military service promotion posts have been on the Russian social network VK since January 2022. Then we identified ads that targeted non-Russian citizens since early 2023. They found that, by mid-2025, one in three contract announcements was aimed at foreigners – a sharp increase from 2024, when such posts made up only about 7% of all advertisements. Since summer 2025, calls for foreigners to join the Russian army have increased more than sevenfold; the estimated numbers are around 4.5 thousand.

One of the most disturbing aspects is what happens after death. Foreign recruits are frequently listed as missing rather than killed. This bureaucratic manoeuvre allows the system to avoid responsibility. Families receive no compensation, no official explanation, and often no confirmation of fate. The individual disappears into paperwork, becoming another invisible casualty of a war that increasingly relies on anonymity.

This practice also reveals something larger about contemporary warfare. Wars today are not only fought for territory or influence. They serve economic, political, and institutional interests. Recruitment campaigns generate money for intermediaries, relieve domestic manpower pressure, and help construct narratives of international support. When foreign fighters are involved, losses are easier to absorb politically. There are fewer questions at home, fewer protests, and less public accountability.

The scale of this phenomenon is striking. Tens of thousands of foreign fighters from dozens of countries have reportedly been recruited since the war began. Some governments have openly protested, urging Russia to stop recruiting their citizens. Others have warned that participation violates national and international law. These appeals, however, have had little visible effect. The logic of the system appears stronger than diplomatic pressure.

This raises an uncomfortable question: when does this model end? History suggests that wars built on mass expendability eventually exhaust not only armies, but societies. The Second World War demonstrated that even “victory” achieved through limitless sacrifice leaves deep scars that last for generations. Repeating that logic in the twenty-first century, under the guise of contracts and advertisements, does not make it less destructive. It only makes it more cynical.

At the same time, this situation illustrates a broader truth about the modern world. War has become intertwined with markets, migration, inequality, and information warfare. People are recruited not because they believe in grand ideas, but because they need money, safety, or legal status. When survival itself becomes negotiable, war ceases to be a national endeavour and turns into an industry.

Ultimately, this recruitment strategy reflects a deeper issue than manpower shortages alone. It reveals a conception of war in which sustainability is measured not by human cost, but by the ability to continuously replace losses. The question, then, is not whether this approach can deliver short-term battlefield results, but how long it can persist before it corrodes everything around it: trust, legitimacy, and the very idea that modern warfare can ever be reconciled with human dignity.

Wars today are often justified through geopolitics and strategy, but the persistence of such practices reminds us that, beneath the rhetoric, old habits endure. The longer they do, the clearer it becomes that the true cost of war is not only counted in territory gained or lost, but in how casually human lives are fed into the machine.

Understanding this reality is essential. Not to moralise, and not to simplify complex geopolitical conflicts, but to recognise that behind every recruitment post and every promised contract stands a system that treats human lives as a renewable resource. History shows where such systems lead. The question is not whether this model can produce short-term battlefield results, but how much human destruction it will normalise before it collapses under its own weight.

Here we are to serve you with news right now. It does not cost much, but worth your attention.

Choose to support open, independent, quality journalism and subscribe on a monthly basis.

By subscribing to our online newspaper, you can have full digital access to all news, analysis, and much more.

You can also follow AzerNEWS on Twitter @AzerNewsAz or Facebook @AzerNewsNewspaper

Thank you!