China’s great leap backward

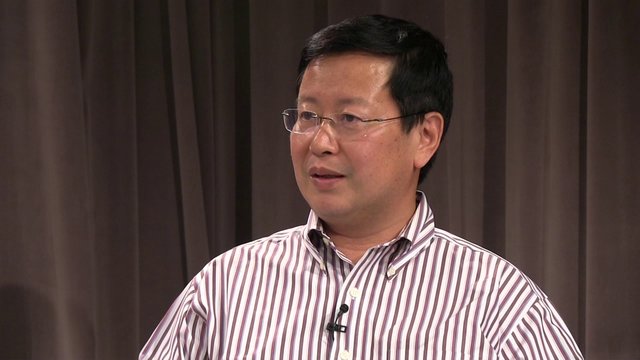

By Xia Yeliang

former professor of economics at Peking University, is a visiting fellow at the Cato Institute.

This week, Chinese Communist Party (CCP) leaders are meeting in Beijing for a plenary session centered on one topic: the rule of law. Yet, in recent days, several groups on WeChat (a popular Chinese social network) have described the arrests of nearly 50 Chinese activists who support the protests in Hong Kong. Others have reported on an official order to ban the publication or sale of books by authors who support the Hong Kong protests, human-rights activism, and the rule of law. This casts serious doubt on the credibility of the government's commitment to its stated goal of political modernization.

Among the banned authors is the economist Mao Yushi, who received the Milton Friedman Prize for Advancing Liberty in 2012. This is not the first time that Mao's books have been banned. In 2003, his work was proscribed after he signed a petition appealing to the government to exonerate the student protesters whose democratic movement ended with the 1989 Tiananmen Square massacre.

China often does not even issue an official public notice of censorship; an "anonymous" phone call to a publisher, understood to be from an official agency, will suffice. A couple of articles in one of my own books were deleted without an official explanation, and phrases, sentences, and even paragraphs have regularly been removed from my columns and commentaries in journals and newspapers.

Another respected author, the 84-year-old Yu Ying-shih, is also under siege for his support of the Hong Kong protests. Yu, who has taught in the United States at a string of Ivy League universities, has been a prolific critic of the CCP for more than five decades.

In his books, Yu criticizes China's traditional culture and classical philosophy, and advances universal values based on Western scholarly tradition. Though the books contain no direct reference to contemporary political issues, China's government views them as critical of CCP rule and thus damaging to social stability.

Then there is Zhang Qianfan, a cautious and prudent scholar, who serves as Vice President of the China Constitutional Law Association. Zhang's moderate approach to political analysis - during our time as colleagues at Peking University, Zhang criticized some of my stances as excessively derogatory toward the current regime - makes him a somewhat surprising target for the government.

Zhang opposes the decision by many of his contemporaries (including me) to support the protests in Hong Kong, fearing that the government will resort to violent repression, as it did in 1989. Given this, the banning of Zhang's books most likely resulted not from his views on the protests, but from the implications of his constitutional research.

Far less surprising was the recent arrest of the well-known activist and human-rights advocate Guo Yushan, who has been involved with many so-called "sensitive" issues over the last decade. In 2012, for example, he played a key role in helping the world-famous blind activist Chen Guangcheng escape from house arrest - a major international embarrassment for China. Nonetheless, the timing of Guo's arrest, shortly before this month's plenary session, highlights the CCP's lack of sincerity when it comes to the rule of law.

The treatment of Chinese dissidents, inside and outside the country, is abhorrent. Either they are jailed for their supposed crimes, or prohibited from visiting their families in China - sometimes for two or three decades.

This is not the fate only of vocal anti-CCP figures. Scholars and researchers - from former Princeton University Professor Perry Link and Columbia University Professor Andrew Nathan to Li Jianglin, a writer and historian focused on contemporary Tibetan history - and even businessmen have been prohibited from returning to China. All it takes to have a visa denied or canceled is to sympathize with human-rights movements in China or express any view that contradicts the CCP's position.

Chinese citizens should be free to leave and enter their homeland, regardless of their political beliefs. Taking away this right without legal justification is a clear violation of modern international norms.

President Xi Jinping's unprecedented anti-corruption campaign was supposed to signify a shift toward a more transparent system, based on the rule of law. But the fact is that the officials who have been purged so far have been Xi's political adversaries, and the entire enterprise has served to consolidate his power.

This duplicity is also evident in the crackdown on freedom of speech, assembly, association, and movement now unfolding in China. Xi appears to be pulling China backwards politically, even as he seeks to drive it forward economically.