Grumpy wife Louisa did John Quincy Adams no favors

By Bloomberg

Wig? Furry hat? What about flannel underwear?

On daily constitutionals through freezing St. Petersburg, John Quincy Adams (1767-1848) often encountered Alexander I, similarly engaged. The emperor (pro-wig, anti-flannel) liked chatting with the American diplomat, who spoke fluent French, the language of the court. Adams’s bald pate concerned him.

Reading of these informal meetings in the splendid “The Remarkable Education of John Quincy Adams” by Phyllis Lee Levin, you can picture the portly minister and the tall royal squinting into the winter sun reflecting off the Neva River.

Not much later, Adams interviewed survivors of Napoleon’s disastrous invasion and ruminated on the little Corsican’s reversal of fortune. His diaries -- kept for some 60 years -- bulged with description of dinners, battles, endless negotiations and perilous voyages in leaky boats.

Adams’s son pruned most personal details to focus on the grand events in his father’s political life. Levin’s biography restores the countless details that humanize the sixth president. His sickly wife Louisa makes frequent appearances, usually to complain. He weeps at the loss of their young daughter.

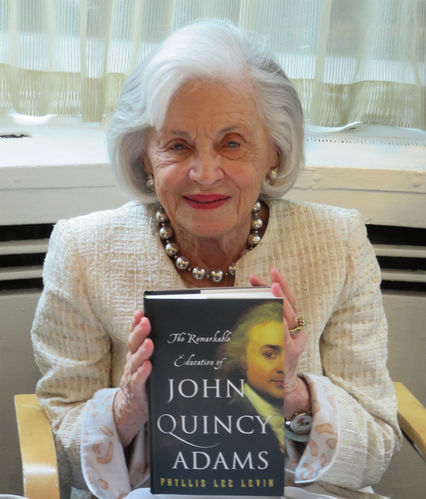

I visited Levin, 93, in her Manhattan apartment whose striped wallpaper and delicate furniture would have pleased Abigail Adams -- John Quincy’s mother, and the subject of an earlier biography.

Misery Is Me

Hoelterhoff: How did you know so much had been dropped from the original diaries?

Levin: In the course of reading the letters of Abigail Adams, I became quite entranced by this intelligent and put-upon young man who went to Europe at the age of 10.

All the charming or intimate things that led you to understand him better had been dropped. Every time the son skipped a date, I knew I had to go back in the diary.

Hoelterhoff: Louisa did him no favors penning “Adventures of a Nobody,” which she said was her autobiography.

Levin: None. What she wrote was brilliantly appalling and wrong but busied a whole generation of feminist studies. Her misery is blamed on his supposed lack of warmth. In fact, he was caring. One day during his presidency, he wrote about how upset he was because she was suffering so and he was meant to be joyous.

Hoelterhoff: She just can’t stop complaining, especially about money. Still, it is surprising that a man so well- connected was always struggling to be properly garbed and housed. He jokes with Alexander about the need to keep up appearances and then has to fire a cook in St. Petersburg.

Levin: Her father had gone bankrupt and she had no dowry. That obsessed her until the end of her life. Perhaps a dowry might have made a difference, but I did lose patience with her after a while -- and we trimmed a lot!

Hoelterhoff: Your book stops when John Quincy returns from decades abroad to become Monroe’s secretary of state and then president. Like his father, he only served one term. What happened?

Poison Politics

Levin: He thought it was undignified to campaign. It wasn’t that he lacked ideas, but it hadn’t been a successful presidency. For instance, he had wanted to build the infrastructure that would open up America, the bridges and roads.

Hoelterhoff: I got the sense that D.C. politics were as poisonous as today?

Levin: At least. He made a marvelous address for unity, but he had forceful enemies, especially Jackson, who had won the popular vote and thought he should have been president.

Hoelterhoff: Instructions and letters from home might take six months and he had to take initiative. Of his diplomatic achievements, which would you rank high?

Levin: The Monroe Doctrine. The issue of neutrality, a core and heartfelt belief of John Quincy’s, resonated most famously in the epic Monroe Doctrine, which has been, on occasion, attributed to his authorship.

The Amistad

Hoelterhoff: You include a revealing letter he sent to his father when he was 14 and observed peasants being sold like beasts in Riga. As an old man, he wins freedom for the Africans enslaved aboard the Amistad in an impassioned speech to the Supreme Court.

Levin: John Quincy’s passionate pronouncements against slavery articulated in letters, notes, in Congress are as compelling as Lincoln’s wording in his Emancipation Proclamation. It’s stunning to me that he is so forgotten. He followed his conscience and his heart.

Here we are to serve you with news right now. It does not cost much, but worth your attention.

Choose to support open, independent, quality journalism and subscribe on a monthly basis.

By subscribing to our online newspaper, you can have full digital access to all news, analysis, and much more.

You can also follow AzerNEWS on Twitter @AzerNewsAz or Facebook @AzerNewsNewspaper

Thank you!