Painting the world for people who don’t see color

By Karla Pequenino

Publico, Portugal

For more than 19 years, Tiago Santos did not understand colors. As a child, growing up in Santa Maria da Feira, a city in the north of Portugal, he had trouble choosing the right crayons. It seemed so easy for others, but when he tried coloring brown trees or blue skies, his classmates laughed at the crayons he chose.

“I thought I did not ‘get’ colors, just like some people struggle with understanding math,” Santos, now 34, said. “I was embarrassed, so I never told people.”

Today, Santos knows he suffers from daltonism, which is a genetic form of colorblindness that prevents him from telling certain colors apart. While most people can spot around 30,000 shades, people with daltonism can identify up to 800. But when Santos was young, people did not talk about colorblindness in Portugal. The boy often used to leave his crayons at home on purpose, so he could ask his friends to pass him the right ones and avoid being bullied.

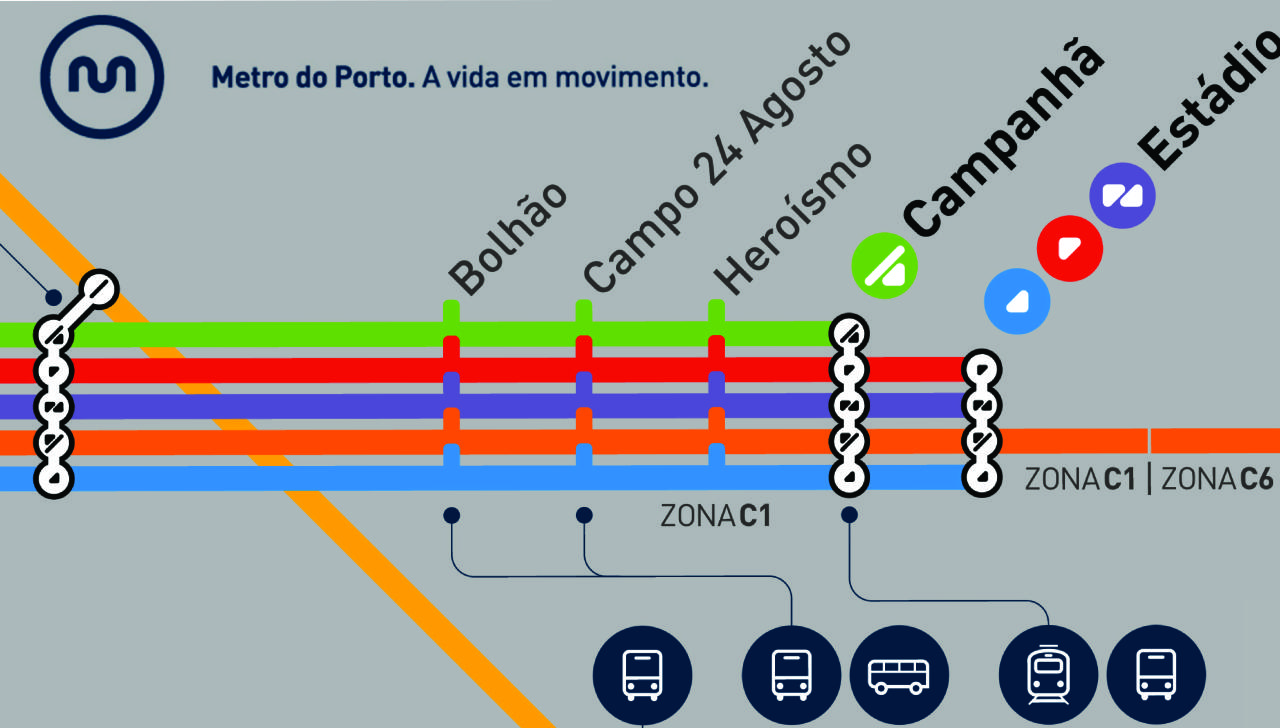

Choosing ripe fruit, matching clothes, and understanding the subway lines were other big challenges. Santos finally learned why he had such a difficult time when he arrived at university and had to ask for help drawing maps during history exams. Being diagnosed did not make his life any easier.

“I spent another 10 years pretending there was nothing wrong with me to avoid asking for help all the time,” Santos said, adding that he felt ashamed of having a condition that few people understood. “ColorADD changed that.”

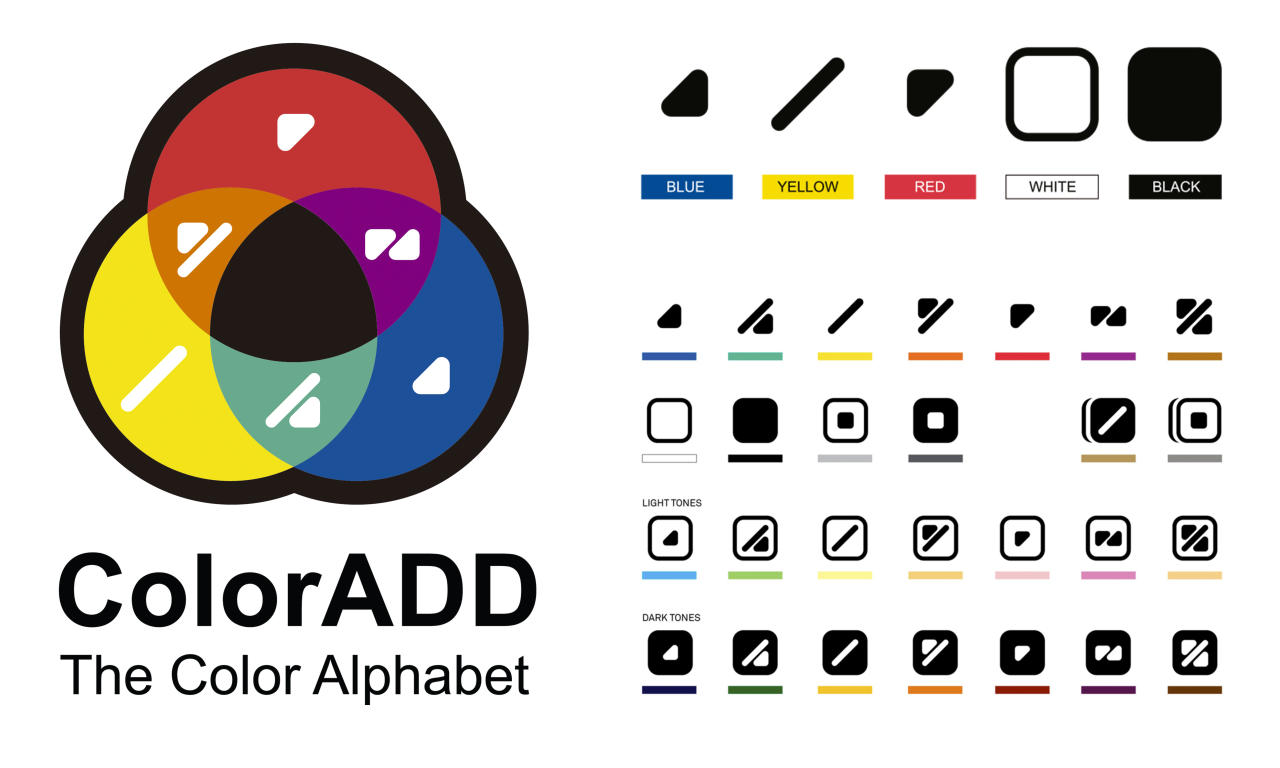

In 2008, a Portuguese designer named Miguel Neiva presented a new system to identify different colors through shapes as part of his Masters dissertation at the University of Minho, in Portugal. With ColorADD, each of the three primary colors (red, yellow and blue) is linked to a basic geometric shape (triangle, slash and inverted triangle). By combining different symbols, it is possible to recognize different colors; orange is represented by a triangle with a slash (the combination of red and yellow).

Neiva, 49, said it took him years to perfect the system. He has never struggled with identifying colors, but is familiar with Tiago’s childhood story. “I had a kid like that in my classroom and I was part of the group that used to laugh at him. Children have a cruel innocence about things they do not understand,” Neiva said. “At the time, only referees who were criticized for giving red cards to soccer players were described as colorblind. I developed a phobia of becoming like that.”

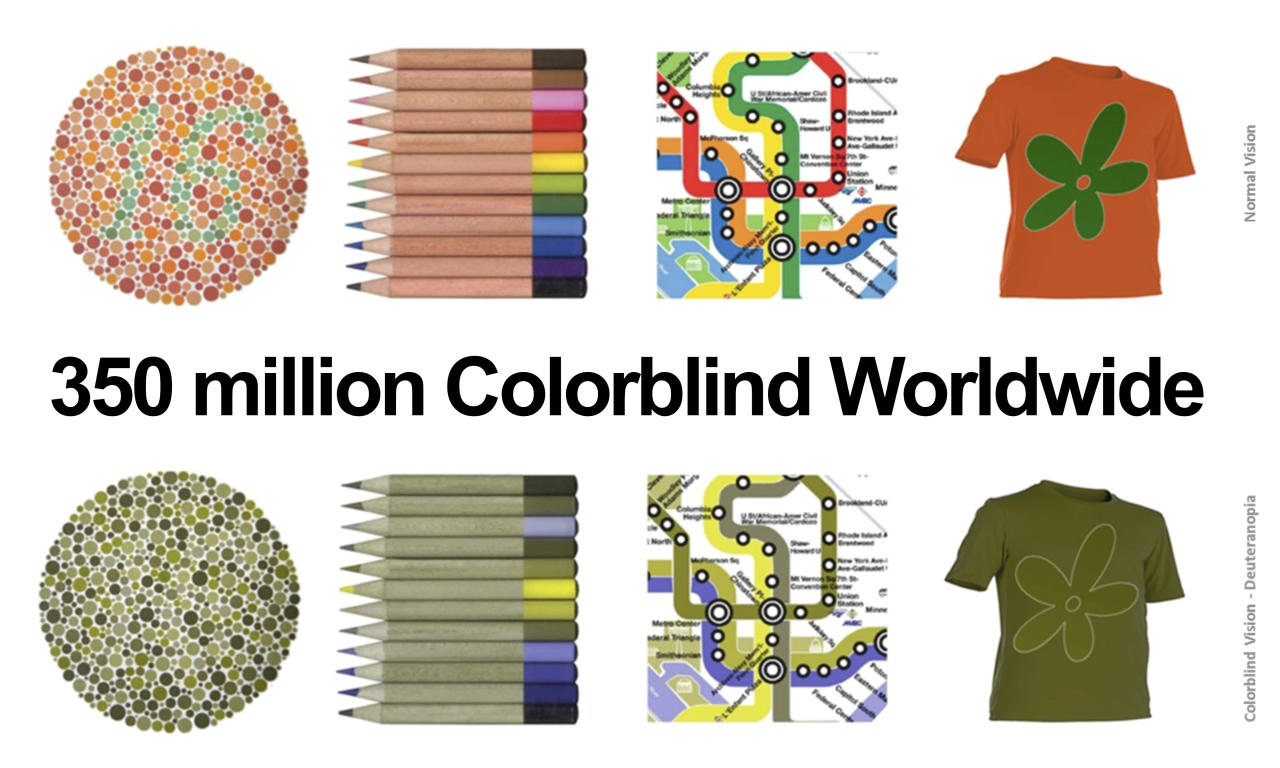

As a designer, Neiva needs to be able to distinguish different shades. Colorblindness affects approximately one in every 12 men and one in 200 women around the world. “It seems little, but in a classroom with 14 boys, up to two of them can have this problem,” explained Neiva. He spent eight years interviewing colorblind people all over the world to create what he calls his “special alphabet.”

Today, ColorADD is included on the garment labels of several Portuguese brands, on colored pencils for children, on card games and transport systems. In 2014, a group of Portuguese programmers even used it to create an iPhone app to label colors automatically through a smartphone camera. It was praised by the United Nations for its global impact.

“More than a code, the projects that come from ColorADD made it possible for me to stop hiding my condition. They give me independence in a society that lives by colors,” said Santos, who is one of the people who uses the smartphone app daily. “Miguel Neiva’s system also helps me talk about colorblindness with people who don’t know about it.”

Companies and institutions that want to use ColorADD in their product pay a license fee, but there is a pro-bono version available for schools and universities. The money goes to ColorADD Social, a project that takes Neiva’s new alphabet to schools and libraries all around the world.

But the designer believes there is still a lot of work to be done. Many subway systems do not use ColorADD, the new iOS 11.9 updates are interfering with the iPhone app, and there is no Android version. “The challenge is keeping this project relevant. People say they like innovation, but nobody likes change that much,” explained Neiva. “ColorADD could have been invented hundreds of years ago. It doesn’t depend on modern technology, and it is easy to learn.”

The Portuguese designer uses partnerships with big brands to raise awareness. The new deck of Uno cards for colorblind gamers, which was created with the help of Mattel, is an example. “But I don’t want to create special products for colorblind people. I want everyone to understand colors,” said Neiva. “The fact that I am not colorblind myself is one of the reasons why the alphabet works. There are several types of colorblindness, but my code solves all of them because I did not focus on a specific version. As humans, we’re at our best when we focus on helping others.”

Here we are to serve you with news right now. It does not cost much, but worth your attention.

Choose to support open, independent, quality journalism and subscribe on a monthly basis.

By subscribing to our online newspaper, you can have full digital access to all news, analysis, and much more.

You can also follow AzerNEWS on Twitter @AzerNewsAz or Facebook @AzerNewsNewspaper

Thank you!