From Baku’s sacrifice to Yerevan’s statues: Tale of two WWII legacies

In a world shaped by the ashes of World War II, the line between memory and manipulation grows increasingly thin. For nations that stood against fascism, the fight was more than geopolitical—it was existential. Azerbaijan, a then-Soviet republic, was one such nation whose contributions to the victory over fascism remain both underrepresented and underappreciated. In stark contrast, neighboring Armenia has, disturbingly, moved in the opposite direction, whitewashing the legacy of Nazi collaborators and erecting monuments to their memory.

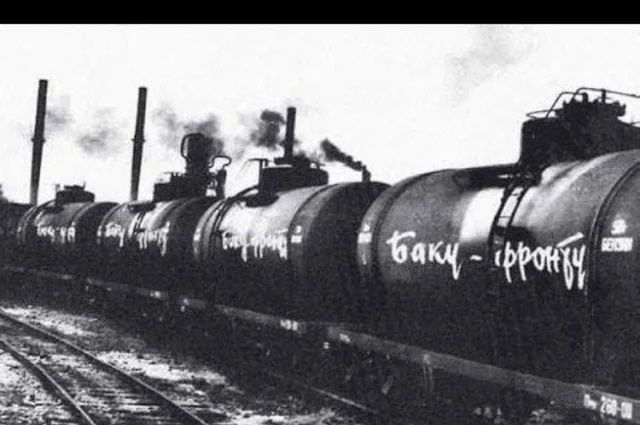

Azerbaijan’s role in the defeat of fascism was not symbolic. It was visceral, costly, and heroic. More than 600,000 Azerbaijani soldiers were mobilized to fight against Nazi Germany. Of them, over 300,000 never returned home. These weren’t mere numbers—they were fathers, sons, and brothers who perished on the blood-soaked battlefields of Eastern Europe. Azerbaijan’s sacrifices were not limited to manpower. Soviet Azerbaijan provided 75–80% of the fuel consumed by the Red Army. The oil fields of Baku quite literally powered the Soviet war machine, and by extension, the Allied cause. More than 130 military formations were raised in Azerbaijan, with 123 receiving honorary titles for bravery. Industrial plants in Baku operated around the clock, and ordinary citizens donated over 70 million rubles to the Soviet war effort, a staggering contribution from a nation already drained by the demands of war.

While Azerbaijan bled to resist fascism, a very different story was unfolding across the border. Tens of thousands of Armenians fought under the banner of Nazi Germany, notably in the Armenian Legion commanded by General Drastamat Kanayan, also known as Dro, and his associate Garegin Ter-Arutyunyan—infamously known as Garegin Nzhdeh. Nzhdeh did not merely collaborate with the Nazis; he actively supported their ideology, fighting against Soviet forces in the Balkans and aligning himself with Hitler's regime in the hope of creating a fascist Armenian state.

This fascist chapter of Armenian history has not been buried in shame, it has been resurrected. The seeds of Armenia’s fascist policy against its neighbours, sown by Garegin Nzhdeh, bore fruit in 1988, on the brink of the Soviet Union’s collapse. This is not a trivial matter of conflicting historical narratives. The glorification of fascist collaborators in Armenia reflects a broader political culture that has, over decades, flirted with ultranationalism and racial exclusivity. As the Soviet Union neared collapse, Armenia witnessed the rise of figures with fascist leanings. These ideologues laid the groundwork for policies that marginalised ethnic minorities and romanticised Armenia’s fascist past, embedding it into the nation’s political fabric.

Under the guise of “reunification,” Armenian nationalists launched a campaign to annexe Garabagh, triggering mass expulsions of Azerbaijanis from both Armenia and Karabakh. But the purge extended beyond Azerbaijanis—Kurds, Meskhetians, and Molokans were also uprooted from their ancestral lands, echoing the ethnic cleansing tactics employed by Nazi Germany in occupied territories. The atrocities committed in Khojaly in 1992, where 613 civilians—many women, children, and the elderly—were brutally massacred, bore chilling resemblance to Nazi massacres in WWII. The strategic targeting of entire communities, not for military reasons but for ethnic erasure, exposes a grim continuity between the ideology Armenia glorifies in figures like Nzhdeh and the wartime horrors the world once vowed never to repeat. Such acts demand global recognition, not diplomatic evasion.

Going further, in 2016, Armenian authorities unveiled a statue of Nzhdeh in the center of Yerevan, elevating a Nazi collaborator to the status of national hero. This move drew sharp criticism not only from the CIS countries and war veterans but also throughout the world. Azerbaijani President Ilham Aliyev also touched on the issue and noted:

“We, the heads of state, have repeatedly spoken out against the glorification of fascists. Unfortunately, such cases occur in the CIS area, especially in Armenia. The former government there erected a statue in central Yerevan to Garegin Ter-Arutyunyan, known as Garegin Nzhdeh—a fascist executioner and traitor who served the German fascists. A large group of war veterans from CIS countries has repeatedly protested this shameless act by Armenia’s former leadership,” President Aliyev stated.

The long-term consequences of this ideological drift became visible during the 2020 Second Garabagh War. That conflict was not only about reclaiming illegally occupied territories, it was also about confronting the ideological descendants of Nzhdeh and Dro. In liberating its lands from Armenian occupation, Azerbaijan delivered a modern-day verdict on fascist revisionism. It was a victory not just of arms, but of historical justice.

Yet, while the world once united in condemning fascism at Nuremberg, today it remains oddly silent about its glorification in Armenia. Western institutions that champion human rights and memory culture have, in many cases, turned a blind eye to Yerevan’s rehabilitation of Nazi-aligned figures. Why is a world that rightly supported the Nuremberg Trials so hesitant to speak out against a statue of a Nazi collaborator in downtown Yerevan? Is the geography of the crime now more important than its nature?

There is an unsettling hypocrisy at play. Azerbaijan’s efforts to spotlight Armenia’s fascist flirtations are often dismissed, while Armenia’s offensive distortion of history receives little more than a diplomatic shrug.

History does not forget, but people do. That is why it is crucial to remind the world of Azerbaijan’s legitimate and valorous place in the history of the fight against fascism. It is equally important to call out the glorification of those who fought for Hitler, regardless of modern political convenience.

The memory of World War II must not be treated as a toolkit to be bent toward nationalist ends. It must be preserved with integrity. Azerbaijan has upheld that integrity, both through its wartime sacrifices and its postwar moral stance. Armenia, by contrast, has chosen to venerate traitors and whitewash atrocities.

In today’s geopolitical landscape, standing against fascism is not only about remembering the past—it is also about shaping the future. Azerbaijan has done both. The world should recognise that, and hold to account those who betray the values of 1945.

Here we are to serve you with news right now. It does not cost much, but worth your attention.

Choose to support open, independent, quality journalism and subscribe on a monthly basis.

By subscribing to our online newspaper, you can have full digital access to all news, analysis, and much more.

You can also follow AzerNEWS on Twitter @AzerNewsAz or Facebook @AzerNewsNewspaper

Thank you!